How Computers Understand Numbers

Introduction

Anyone with some programming experience probably knows that computers operate using 1s and 0s — known as bits. But not everyone understands why we use bits in the first place. In this article, we’ll explore the reasoning behind this design choice and uncover how computers represent information at the most fundamental level.

From Analog to Digital

Information can be represented in two fundamental forms: analog or digital.

Analog (Merriam-Webster): of, relating to, or being a mechanism or device in which information is represented by continuously variable physical quantities

Digital (Cambridge Dictionary): recording or storing information as a series of the numbers 1 and 0, to show that a signal is present or absent.

The real world is analog — continuous, infinitely detailed, and unbroken.

For example, there are infinitely many real numbers between 7.129 and 7.130:

However, computers are built from finite hardware systems. Memory chips, processors, and storage devices can only hold a limited number of bits. Therefore, the challenge is to represent enough of the real world to satisfy our computational needs and our senses — sight, sound, and touch — within these physical limits.

Why Digitize?

Most sensors in the real world — microphones, thermometers, cameras — naturally produce analog signals.

However, computers cannot process analog information directly. To process these signals, we must digitize them — converting continuous analog inputs into discrete digital values.

Side Note

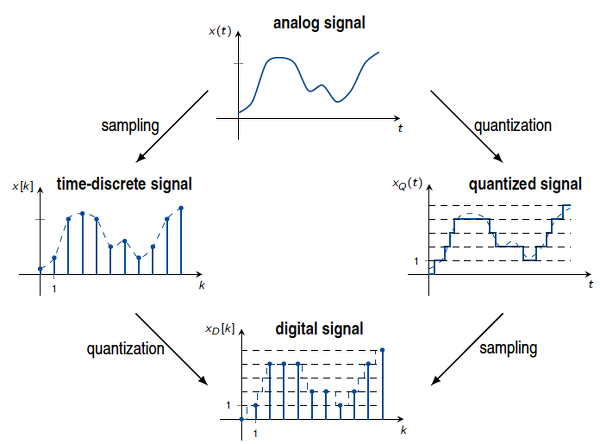

This is where the Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) comes in.

An ADC samples an analog signal at regular intervals and quantizes each measurement into a digital value. Once converted, the data can be stored, processed, or transmitted by a computer.

In short:

- The natural world is analog and continuous.

- Computers are digital and finite.

- Digitization bridges the gap, allowing computers to make sense of the real world.

Now that we’ve seen how the analog world becomes ones and zeros, let’s see how that sparked today’s digital revolution—the Information Age.

Information Age

We’re currently living in the Information Age (wikipedia). During this era, humanity has created countless digital systems — from computers and smartphones to TVs, cameras, and scientific calculators.

Signal

Early computers transmitted signals using relays and vacuum tubes, all operating through electrical signals like voltage and current.

The Birth of the Transistor

In 1947, a groundbreaking device was invented — the transistor — which pioneered and defined the modern semiconductor era. It offered low power consumption, high reliability, and long lifespan, making relays and vacuum tubes obsolete.

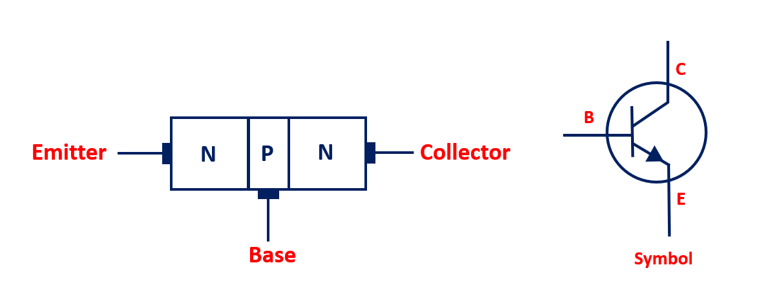

A transistor is a three-terminal semiconductor device. When enough current is applied to the base (B) terminal, current flows from the collector (C) to the emitter (E). From the emitter’s perspective, no current flow represents a 0, while current flow (nonzero voltage) represents a 1.

Nowadays, most digital systems use two discrete values (binary) because it’s easy to implement using transistors that switch between two voltage levels. The two discrete values can be interpreted as:

- digits 0 and 1 (aka. binary digit, or bit)

- Low (L) and High (H) (voltage levels)

- False (F) and True (T) (boolean values)

- On and Off (switches)

Signal Distortion

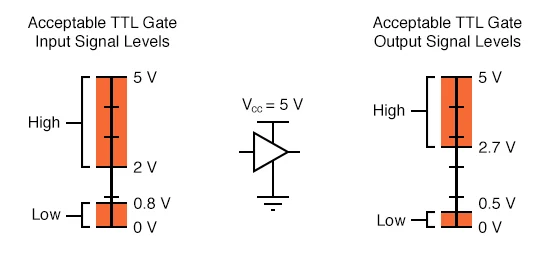

During transmission, signals can become distorted as voltage levels fluctuate, but the binary design inherently provides fault tolerance. The following figure demonstrates the working range of a TTL (Transistor-Transistor Logic) gate:

Its wide operating range is ideal for real-world applications, where electrical noise can interfere with digital devices. However, this comes with a tradeoff: digitization sacrifices some accuracy for greater reliability and easier transmission.

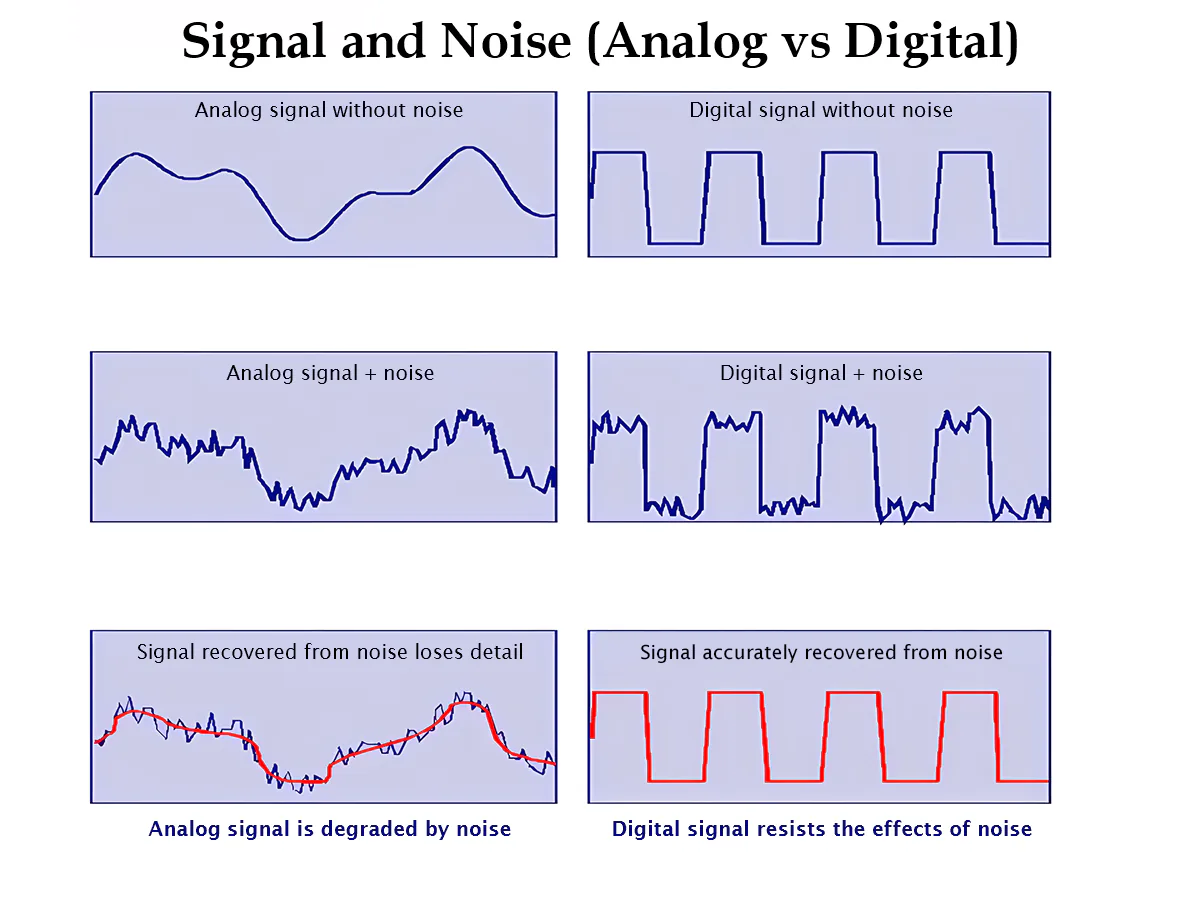

The picture below depicts this tradeoff. As long as a distorted digital signal is still inside the working range, it can recover its original input. In comparison, analog signals are more difficult to recover.

That’s why designers favored binary over decimal or other numeral systems.

In short:

- Modern digital systems use the binary system (only two digits, 1s and 0s), which was implemented using transistors.

- Distinguishing 2 voltage levels is easier and has less distortion than 10 levels for real-world electrical devices.

- Digital signals are easier to recover than analog signals at the cost of accuracy.

This trade-off—simplicity and reliability over continuous precision—led computers to embrace binary. Let’s explore how binary actually works next.

What the Heck is Binary?

Number vs. Numeral

Before we talk about binary, let’s first distinguish numbers from numerals.

A numeral is a written or spoken representation of a number — e.g., 3, three, III, 三, trois. Numerals are built from a consistent sequence of digits or symbols. (That’s why we say Roman numerals, not Roman numbers.)

A number, on the other hand, is the abstract mathematical idea itself — there’s only one concept of 3, even though many different numerals can represent it.

Numeral System

A numeral system, defined by its base (or radix), uses digits or other symbols to represent numbers. The actual quantity a numeral represents is called its value.

The same sequence of symbols may represent different numbers in different bases.

For example, the string “11” means:

- Eleven in the decimal (base-10) system

- Three in the binary (base-2) system

- Two in the unary (base-1) system, used for simple tallying

Decimal Numeral System

The decimal (base-10) system uses digits 0–9. When a column reaches 10, we “carry” to the next column.

A decimal numeral consists of a whole-number part, a fractional part, and a decimal point.

Decimal is positional: each digit’s value equals the digit times a power of 10 determined by its position (Positional notation):

*We sometimes annotate base with a subscript, e.g., $1645.72_{10}$; for decimal, we often omit it.

Binary Numeral System

The binary system (base-2) is the foundation of all digital computing.

The word binary comes from bi-, meaning two. Binary uses only two digits — 0 and 1 — which makes it ideal for computers, since hardware can easily distinguish between two voltage levels (on/off, high/low, true/false).

Everything a computer processes — numbers, characters, colors, music, videos, even your bank balance — can ultimately be represented as sequences of bits. With $N$ bits, we can represent $2^N$ different things.

Like decimal, binary is also positional, but with powers of 2 instead of powers of 10. When a column reaches 2, we carry over.

Binary Numeral Example:

$$ 11001_2 = 1 \times 2^4 + 1 \times 2^3 + 0 \times 2^2 + 0 \times 2^1 + 1 \times 2^0 = 16+8+0+0+1 = 25_{10} $$ASCII Example (character ‘A’):

$$ A = 01000001_2 = 1 \times 2^6 + 1 \times 2^0 = 64 + 1 = 65_{10} $$ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange)

Computers only understand numbers, so ASCII assigns numeric codes to characters (like ‘W’, ‘#’, or ‘!’). Although ASCII originated decades ago, its printable characters remain in use today.

You can check the full ASCII table at asciitable.com. (Unicode is the larger modern superset.)

| Decimal | Binary | Decimal | Binary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0000 | 8 | 1000 |

| 1 | 0001 | 9 | 1001 |

| 2 | 0010 | 10 | 1010 |

| 3 | 0011 | 11 | 1011 |

| 4 | 0100 | 12 | 1100 |

| 5 | 0101 | 13 | 1101 |

| 6 | 0110 | 14 | 1110 |

| 7 | 0111 | 15 | 1111 |

Decimal ↔ Binary (0–15)

Binary numerals, like decimals, can also have fractional parts separated by a binary point:

$$ 101.101_2 = 1 \times 2^2 + 0 \times 2^1 + 1 \times 2^0 + 1 \times 2^{-1} + 0 \times 2^{-2} + 1 \times 2^{-3} = 5 + \tfrac{1}{2} + \tfrac{1}{8} = 5.625. $$Commonly Used Numeral Systems

Aside from decimal and binary, there are a few other numeral systems you’ll often encounter in programming.

Computers internally operate in binary, but long binary strings are hard for humans to read or debug. To make our life easier, we often use hexadecimal (base-16) as compact, human-friendly shortcuts.

Base 10 (decimal)

- Decimal Digits: 0–9

- Usage: Decimal numerals are understandable and extensively used by humans.

- Prefix: none — e.g. 34256

Base 2 (binary)

- Binary Digits: 0, 1

- Usage: Machine-friendly. (Strictly: hardware stores thresholds/levels, not the characters ‘0’/‘1’.)

- Prefix: 0b — e.g. 0b00100111

Base 8 (octal)

- Octal Digits: 0–7

- Usage: Rare today, but historically used in older systems

- Prefix:

0in classic C (e.g.,0174);0oin Python and others (e.g.,0o174).

Base 16 (hexadecimal, or hex)

- Hexadecimal Digits: 0–9, A–F (letters may be uppercase or lowercase)

- Usage: Compact representation of binary values, common in low-level programming and memory addresses

- Prefix:

0x— e.g.,0xFFFF.

Decimal-Binary-Octal-Hexadecimal Conversion Table

| Decimal | Binary | Octal | Hex |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0000 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0001 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 0010 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 0011 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 0100 | 4 | 4 |

| 5 | 0101 | 5 | 5 |

| 6 | 0110 | 6 | 6 |

| 7 | 0111 | 7 | 7 |

| 8 | 1000 | 10 | 8 |

| 9 | 1001 | 11 | 9 |

| 10 | 1010 | 12 | A |

| 11 | 1011 | 13 | B |

| 12 | 1100 | 14 | C |

| 13 | 1101 | 15 | D |

| 14 | 1110 | 16 | E |

| 15 | 1111 | 17 | F |

Nibbles and Bytes

A few quick terms you’ll see often:

- 4 bits = 1 nibble → corresponds to 1 hex digit (16 possible values)

- 8 bits = 1 byte → usually represents a character like ‘D’ or ‘J’

- Two hex digits = one byte = 256 possible values

- Modern CPUs are typically described as 32-bit or 64-bit depending on word size.

Base Conversion

Sometimes we represent binary numbers in other bases (octal or hex) for readability.

Let’s see how to convert between them.

Binary → Decimal

Multiply each bit by its corresponding power of 2 and sum them:

$$ (a_{n-1}\cdots a_1a_0)_2 = a_{n-1}\,2^{n-1} + a_{n-2}\,2^{n-2} + \cdots + a_0\,2^0 $$Note: positions start at 0 for the LSB and go up to $n-1$.

Example:

$$ (11101011)_2 = 128+64+32+8+2+1 = 235_{10} $$The same principle applies to any base — multiply each digit by its base raised to the digit’s position power.

Binary → Octal

Group bits in sets of three (from right to left) and convert each group to an octal digit:

Example:

$$ (11101011)_2 = (011 \space 101 \space 011)_2 = (3 \space 5 \space 3)_8 = (353)_8 $$Binary → Hexadecimal

Group bits in sets of four (from right to left), then convert each to a hex digit:

Example:

$$ (1110101101101)_2 = (1\;1101\;0110\;1101)_2 = (1\;\text{D}\;6\;\text{D})_{16} = (1\text{D}6\text{D})_{16} $$The reverse conversions (octal or hex → binary) simply expand each digit back into its binary equivalent.

Integer Representations

Computers represent integers using bit sequences.

These representations must support integer operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and comparison.

Unsigned Integers

Most modern computers are 64-bit architectures, but many programming languages (like C or C++) still use 32-bit unsigned integers for compatibility or memory efficiency.

If an unsigned integer is 32 bits wide, it can represent $2^{32}$ distinct values — that’s 4,294,967,296 (~4 billion) possible numbers in total, ranging from $0$ to $2^{32}-1$.

In general:

- An N-bit unsigned integer can represent numbers from $0$ to $2^N - 1$.

Example (8-bit unsigned integer):

- $(11111111)_2 = 255_{10}$

Unsigned Integer Ranges by Bit Width:

- 8-bit (1 Byte) → 0–255

- 16-bit (2 Byte) → 0–65,535

- 32-bit (4 Byte) → 0–4,294,967,295

- 64-bit (8 Byte) → 0–18,446,744,073,709,551,615

Now you know how computers represent unsigned integers. Let’s see some arithmetic operations on them.

Binary Arithmetic

Addition

- $0+0=0$ (carry 0)

- $0+1=1$ (carry 0)

- $1+0=1$ (carry 0)

- $1+1=0$ (carry 1)

Example:

$$ (1101)_2 + (1011)_2 = (11000)_2 $$$$ 13 + 11 = 24 $$

Subtraction

Borrow as needed (from the next higher bit):

- $0-0=0$

- $1-0=1$

- $1-1=0$

- $0-1=1$ (borrow 1)

Example:

$$ (1110)_2 - (1011)_2 = (0011)_2 $$$$ 14 − 11 = 3 $$

Multiplication

Works the same way as decimal long multiplication:

- $0 \times x = 0$

- $1 \times x = x $

Example:

$$ (101)_2 \times (11)_2 = (1111)_2 $$$$ 5 × 3 = 15 $$

Division

Also similar to decimal long division:

$$ (11011)_2 \div (11)_2 = (1001)_2 $$$$ 27 ÷ 3 = 9 $$

In short:

- The basic arithmetic operations just work like in decimal, but the digits only have 1 and 0, and we carry over when reaching 2.

You might wonder what happens when an unsigned integer goes beyond its maximum/minimum value? That’s where overflow comes in.

Overflow

Strictly speaking, binary numerals can have an infinite number of digits.

However, real hardware has physical limits — we can’t store infinite bits.

When the result of an arithmetic operation exceeds the range that the available hardware bits can represent, we say that an integer overflow has occurred.

For example, suppose our hardware can only store 4 bits.

If we add 1 to 0b1111 (4-bit), overflow occurs.

In an ideal infinite-bit world, the result would be 0b10000, but since our hardware only keeps 4 bits, the leftmost bit (called the Most Significant Bit, or MSB) is discarded.

The stored result becomes 0b0000 (0), even though the true mathematical result is 16.

This happens because the number “wraps around” after reaching the largest representable value.

We can also have what’s sometimes called negative overflow (not to be confused with underflow, which means something different in floating-point arithmetic).

Negative overflow happens when we go below the smallest representable value.

For instance, subtracting 1 from 0b0000 (4-bit unsigned) wraps to 0b1111 (15), not −1.

In short:

- Positive overflow: result too large → wraps around to 0

- Negative overflow: result too small → wraps around to the maximum value

So far, we’ve discussed how to work with unsigned integers. Let’s move on to signed integers.

Signed Integers

Unlike unsigned integers, signed integers can represent both positive and negative numbers.

There are several common ways to represent signed integers in binary:

- Sign–Magnitude

- One’s Complement

- Two’s Complement

- Bias Encoding

Sign-Magnitude

We’ve been using sign–magnitude representation since grade school.

The sign determines whether the number is positive or negative, while the magnitude represents the size of the number:

We can transfer this same idea to the binary system.

Since computers store data in bits, we can reserve one bit to represent the sign — typically the Most Significant Bit (MSB) — where:

0→ positive1→ negative

Thus, an N-bit sign–magnitude number can represent values from:

$$ -(2^{N-1} - 1) \text{ to } +(2^{N-1} - 1) $$Formally:

$$ x = (-1)^s \times |N| = \begin{cases} (0\,N)_2, & \text{if } s = 0 \text{ (positive)} \\ (1\,N)_2, & \text{if } s = 1 \text{ (negative)} \end{cases} $$Where:

- \( s \) — sign bit (stored as the MSB)

- \( N \) — magnitude bits

Example:

$$ \begin{aligned} -10 &= (-1)^1 \times |10| = (1\,1010)_2 \\ +10 &= (-1)^0 \times |10| = (0\,1010)_2 \end{aligned} $$Sign–Magnitude Representation (4-bit Example):

| Sign Bit (MSB) | Magnitude | Binary Form | Decimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 000 | 0000 | +0 |

| 0 | 001 | 0001 | +1 |

| 0 | 010 | 0010 | +2 |

| 0 | 011 | 0011 | +3 |

| 0 | 100 | 0100 | +4 |

| 0 | 101 | 0101 | +5 |

| 0 | 110 | 0110 | +6 |

| 0 | 111 | 0111 | +7 |

| 1 | 000 | 1000 | -0 |

| 1 | 001 | 1001 | -1 |

| 1 | 010 | 1010 | -2 |

| 1 | 011 | 1011 | -3 |

| 1 | 100 | 1100 | -4 |

| 1 | 101 | 1101 | -5 |

| 1 | 110 | 1110 | -6 |

| 1 | 111 | 1111 | -7 |

Drawbacks of Sign–Magnitude

While intuitive, sign–magnitude has some limitations:

- Two representations of zero (

+0and−0) — this adds unnecessary complexity. - Arithmetic is inconsistent — simple addition and subtraction often produce incorrect results.

- Hardware inefficiency — different circuits are needed for addition and subtraction.

Example:

$$ 7 - 4 = 7 + (-4) = (0111)_2 + (1011)_2 $$$$ \begin{array}{cccc} & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ +& 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ \hline & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 &\ne 3_{10} \end{array} $$

Even a simple subtraction can fail.

To make sign–magnitude arithmetic work, we’d need conditional logic:

- If signs match → add magnitudes and keep the sign

- If signs differ → subtract the smaller magnitude from the larger, and take the sign of the larger

That’s just too complicated — so let’s move on to better solutions.

One’s Complement

In one’s complement, the MSB is still the sign bit — but the idea for negatives is simpler:

To represent a negative number, flip all the bits (complement) of its positive counterpart.

Example:

+7 = 0b0000_0111

−7 = 0b1111_1000

Observations:

- Positive numbers start with leading

0s - Negative numbers start with leading

1s - Two zeros still exist:

0000 0000(+0) and1111 1111(−0) - Arithmetic is somewhat simplified but still not perfect

Advantages:

- Easy to get the negative by flipping bits

- MSB still acts as a sign bit

Disadvantages:

- Still has two zeros

- Arithmetic requires manual “end-around carry” adjustments

One’s Complement Arithmetic

Let’s see how arithmetic works in one’s complement, using 4-bit examples.

Example 1: Addition $(5 + (-3))$

$+5 = 0101_2$, $-3 = 1100_2$ (flip 0011)

$$ 0101 + 1100 = 10001_2 \quad (\text{carry out} = 1) $$

Add the carry back (end-around carry):

$$ 0001 + 1 = 0010_2 $$Result: $5 + (-3) = 2$

Example 2: Subtraction $(7 - 5)$

$+7 = 0111_2$, $+5 = 0101_2$

Use one’s complement: $-5 = 1010_2$

$$ \begin{array}{ccccc} & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ +& 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ \hline 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array} $$$$ 0111 + 1010 = 10001_2 \quad (\text{carry out} = 1) $$

Add the carry back:

$$ 0001 + 1 = 0010_2 $$Result: $7 - 5 = 2$

Two’s Complement

The main problem with one’s complement is double zero and awkward arithmetic.

Two’s complement fixes this by shifting the negative range one step further.

To compute a negative number:

- Complement (flip) all bits

- Add 1

Example (4-bit, negate +5):

$$ (0101)_2 \xrightarrow{\text{flip}} (1010)_2 \xrightarrow{+1} (1011)_2 \quad (= -5) $$Advantages:

- Only one zero

- Arithmetic “wraps around” naturally (no special logic)

- Simple hardware: same adder works for both positive and negative numbers

- MSB still represents the sign

- Continuous counting order (binary odometer effect)

Range of representable values:

$$ [-2^{N-1}, +2^{N-1}-1] $$Overflow in two’s complement can be visualized as a number wheel, where the sequence wraps around after the extremes.

Two’s Complement Arithmetic

Example 1: Addition

Compute \( 5 + (-3) \) using 4-bit two’s complement.

-

Represent both numbers in 4 bits:

\( +5 = 0101_2 \)

\( -3 = 1101_2 \) (flip bits of0011→1100, then add1→1101) -

Add them together:

$$ \begin{array}{ccccc} & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 \\ +& 1 & 1 & 0 & 1 \\ \hline 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \end{array} $$ -

Drop the carry-out (leftmost bit):

Result =0010= +2

Result: \( 5 + (-3) = 2 \)

Example 2: Subtraction

Compute \( 7 - 5 \) using two’s complement addition.

-

Represent both numbers in 4 bits:

\( +7 = 0111_2 \)

\( +5 = 0101_2 \) -

To subtract, add the two’s complement of the subtrahend:

\( -5 = 1010 + 1 = 1011_2 \) -

Perform addition:

$$ \begin{array}{ccccc} & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ +& 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ \hline 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \end{array} $$ -

Drop the overflow carry:

Result =0010= +2

Result: \( 7 - 5 = 2 \)

Comparison of Signed Integer Representations (4-bit)

| Decimal | Sign–Magnitude | Two’s Complement | One’s Complement |

|---|---|---|---|

| +7 | 0111 | 0111 | 0111 |

| +6 | 0110 | 0110 | 0110 |

| +5 | 0101 | 0101 | 0101 |

| +4 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 |

| +3 | 0011 | 0011 | 0011 |

| +2 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 |

| +1 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 |

| +0 | 0000 | 0000 | 0000 |

| -0 | 1000 | – | 1111 |

| -1 | 1001 | 1111 | 1110 |

| -2 | 1010 | 1110 | 1101 |

| -3 | 1011 | 1101 | 1100 |

| -4 | 1100 | 1100 | 1011 |

| -5 | 1101 | 1011 | 1010 |

| -6 | 1110 | 1010 | 1001 |

| -7 | 1111 | 1001 | 1000 |

| -8 | – | 1000 | – |

Note:

- At 4 bits, two’s complement has one extra negative (−8), which is why the range is asymmetric.

Only two’s complement provides:

- A single representation of zero

- Seamless arithmetic (no extra workaround)

Bias Encoding

Two’s complement is efficient for arithmetic, but not ideal for all contexts. It has a few quirks:

0b0000doesn’t represent the smallest possible value- The range is asymmetric (one extra negative number)

- The midpoint isn’t zero

For other use cases, we use bias/offset encoding (also called offset binary).

Motivation

Imagine an electrical signal that ranges from 0 V to 15 V.

How can we represent both negative and positive values using only this positive range?

That’s where bias comes in — we simply shift the range of numbers so that zero sits in the middle.

Concept

Bias encoding works by adding or subtracting a constant bias value.

Formally (let \(B = 2^{N-1}-1\) be the bias):

- To interpret a stored value: $$ \text{Number} = \text{Unsigned} - B $$

- To store a real number: $$ \text{Unsigned} = \text{Number} + B $$

This allows us to map purely positive binary patterns to values that span both negative and positive ranges.

Example

Let’s use a 4-bit system.

With 4 bits, there are \( 2^4 = 16 \) possible unsigned values (0–15).

If we want zero centered for 4 bits, choose a bias \(B = 7\) (since \(2^{4-1}-1=7\)):

So for \( N = 4 \):

$$ B = 2^{3} - 1 = 7 $$This means:

- Stored value

0→ represents −7 - Stored value

7→ represents 0 - Stored value

15→ represents +8

Key Idea

Bias encoding lets you reinterpret unsigned numbers as shifted signed values — simply by offsetting the origin.

And the bias doesn’t even have to be −7; it can be anything depending on your application.

For example, with 4 bits you could represent numbers 800–815 by using a bias of +800.

This will become useful when we learn floating-point numbers in the future.

Summary

In short: Everything inside a computer is represented as bit sequences.

| Property | Unsigned | Sign–Magnitude | One’s Complement | Two’s Complement | Bias (Offset) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Handling | N/A | MSB = sign | Flip bits | Flip bits + 1 | Subtract bias |

| Easy Arithmetic | ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Single Zero | ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Widely Used | ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | It depends |

| Smallest Value | 0 | −(2ⁿ⁻¹ − 1) | −(2ⁿ⁻¹ − 1) | −2ⁿ⁻¹ | −B |

| Largest Value | 2ⁿ − 1 | +(2ⁿ⁻¹ − 1) | +(2ⁿ⁻¹ − 1) | +(2ⁿ⁻¹ − 1) | (2ⁿ − 1) − B |